According to the American Cancer Society, breast cancer is the second most common cancer among American women after skin cancers. They estimate that 1 in 8 women will develop invasive breast cancer during their lifetimes.

On a positive note, death rates from breast cancer have been declining since 1989, probably due to earlier detection and improved treatments, and there are currently more than 2.8 million breast cancer survivors in the US.

However, the American Cancer Society estimates that 39,620 women will die from the disease in 2013 - a 1 in 36 chance.

Current treatment options include intravenous chemotherapy, radiation and surgery. While beneficial, these treatments can produce unpleasant side effects, and the body needs a period of time to rest and recover between treatments.

The researchers, all from Harvard, point out that intra-nipple injections spare other parts of the body.

Dr. Silva Krause, one of the researchers behind the experiments, explains:

Another advantage of this procedure is that the injections can be

repeated weekly or bi-weekly over several months without damaging the

nipple.

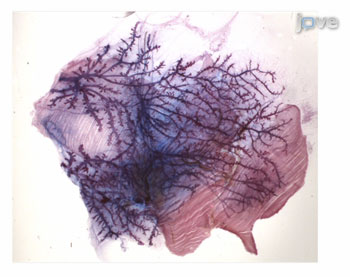

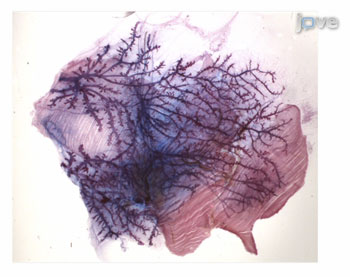

Researchers injected live mice under anesthesia with Evans blue dye to help people understand the technique. The dye filled the entire ductal tree of the mammary gland, making it easily visible to the eye.

They claim that this technique is adaptable for a variety of compounds, including chemotherapeutic agents, siRNA (small interfering RNAs that can silence specific genes) and small molecules.

But the researchers warn that the effectiveness of this transmission method does depend a lot on the operator.

Perforating the duct, for example, will deliver the drugs to the mammary fat pad, while if the solution is injected too fast, it may damage the cells lining the ducts and provoke an inflammatory response.

According to Dr. Krause, she and her colleagues are continuing their research.

"The authors have utilized this technique to inject a new nanoparticle-based therapeutic that inhibits a specific gene that drives breast cancer formation.

This targeted treatment was shown to prevent cancer progression in mice that spontaneously develop mammary tumors."

On a positive note, death rates from breast cancer have been declining since 1989, probably due to earlier detection and improved treatments, and there are currently more than 2.8 million breast cancer survivors in the US.

However, the American Cancer Society estimates that 39,620 women will die from the disease in 2013 - a 1 in 36 chance.

Targeting the milk ducts

Most breast cancers originate in cells lining the milk ducts - the thin tubes that carry milk from the milk glands (lobules) to the nipple. Injections via the nipple directly target this area, delivering the drugs where they are needed most.Current treatment options include intravenous chemotherapy, radiation and surgery. While beneficial, these treatments can produce unpleasant side effects, and the body needs a period of time to rest and recover between treatments.

The researchers, all from Harvard, point out that intra-nipple injections spare other parts of the body.

Dr. Silva Krause, one of the researchers behind the experiments, explains:

"Local delivery of therapeutic agents into the breast, through intra-nipple injection, could diminish the side effects typically observed with systemic chemotherapy - where the toxic drugs pass through all of the tissues of the body. It also prevents drug breakdown by the liver, for example, which can rapidly reduce effective drug levels."

Most breast cancers originate in the cells lining the milk ducts. By

injecting through the nipple, drugs can be delivered directly to the

affected area. Photo credit: JoVE.

Researchers injected live mice under anesthesia with Evans blue dye to help people understand the technique. The dye filled the entire ductal tree of the mammary gland, making it easily visible to the eye.

They claim that this technique is adaptable for a variety of compounds, including chemotherapeutic agents, siRNA (small interfering RNAs that can silence specific genes) and small molecules.

But the researchers warn that the effectiveness of this transmission method does depend a lot on the operator.

Perforating the duct, for example, will deliver the drugs to the mammary fat pad, while if the solution is injected too fast, it may damage the cells lining the ducts and provoke an inflammatory response.

According to Dr. Krause, she and her colleagues are continuing their research.

"The authors have utilized this technique to inject a new nanoparticle-based therapeutic that inhibits a specific gene that drives breast cancer formation.

This targeted treatment was shown to prevent cancer progression in mice that spontaneously develop mammary tumors."

0 comments:

Post a Comment