History and etymology

The first alcohol (today known as ethyl alcohol) was discovered by the tenth-century Persian alchemist al-Razi.kuḥl (kohl) was originally the name given to the very fine powder produced by the sublimation of the natural mineral stibnite to form antimony sulfide Sb2S3 (hence the essence or "spirit" of the substance), which was used as an antiseptic, eyeliner and cosmetic (see kohl (cosmetics)). Bartholomew Traheron in his 1543 translation of John of Vigo introduces the word as a term used by "barbarous" (Moorish) authors for "fine powder"

The word alcohol appears in English, as a term for a very fine powder, in the 16th century, loaned via French from medical Latin, ultimately from the Arabic الكحل (al-kuḥl, "the kohl, a powder used as an eyeliner".

William Johnson in his 1657 Lexicon Chymicum glosses the word as antimonium sive stibium. By extension, the word came to refer to any fluid obtained by distillation, including "alcohol of wine", the distilled essence of wine. Libavius in Alchymia (1594) has vini alcohol vel vinum alcalisatum.

Johnson (1657) glosses alcohol vini as quando omnis superfluitas vini a vino separatur, ita ut accensum ardeat donec totum consumatur, nihilque fæcum aut phlegmatis in fundo remaneat. The word's meaning became restricted to "spirit of wine" (the chemical known today as ethanol) in the 18th century, and was extended to the class of substances so-called as "alcohols" in modern chemistry, after 1850.

The current Arabic name for alcohol in The Qur'an, in verse 37:47, uses the word الغول al-ġawl —properly meaning "spirit" or "demon"—with the sense "the thing that gives the wine its headiness."

Also, the term ethanol was invented 1838, modeled on German äthyl (Liebig), from Greek aither (see ether) + hyle "stuff." Ether in late 14c. meant "upper regions of space," from Old French ether and directly from Latin aether "the upper pure, bright air," from Greek aither "upper air; bright, purer air; the sky," from aithein "to burn, shine," from PIE root *aidh- "to burn"

Alcoholic beverages has been consumed by humans since prehistoric times for a variety of hygienic, dietary, medicinal, religious, and recreational reasons.

Primary alcohols (R-CH2-OH) can be oxidized either to aldehydes (R-CHO) (eg acetaldehyde as described below) or to carboxylic acids (R-CO2H), while the oxidation of secondary alcohols (R1R2CH-OH) normally terminates at the ketone (R1R2C=O) stage. Tertiary alcohols (R1R2R3C-OH) are resistant to oxidation.

Ethanol's toxicity is largely caused by its primary metabolite; acetaldehyde (systematically ethanal) and secondary metabolite; acetic acid. All primary alcohols are broken down into aldehydes then to carboxylic acids, and whose toxicities are similar to acetaldehyde and acetic acid. Metabolite toxicity is reduced in rats fed N-acetylcysteine and thiamine.

Tertiary alcohols are unable to be metabolised into aldehydes and as a result they cause no hangover or toxicity through this mechanism. Some secondary and tertiary alcohols are less poisonous than ethanol because the liver is unable to metabolise them into these toxic by-products.

This makes them more suitable for recreational and medicinal use as the chronic harms are lower. tert-Amyl alcohol found in alcoholic beverages are a good example of a tertiary alcohol which saw both medicinal and recreational use.

Other alcohols are substantially more poisonous than ethanol, partly because they take much longer to be metabolized and partly because their metabolism produces substances that are even more toxic.

Methanol (wood alcohol), for instance, is oxidized to formaldehyde and then to the poisonous formic acid in the liver by alcohol dehydrogenase and formaldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes, respectively; accumulation of formic acid can lead to blindness or death. Likewise, poisoning due to other alcohols such as ethylene glycol or diethylene glycol are due to their metabolites, which are also produced by alcohol dehydrogenase. An effective treatment to prevent toxicity after methanol or ethylene glycol ingestion is to administer ethanol. Alcohol dehydrogenase has a higher affinity for ethanol, thus preventing methanol from binding and acting as a substrate. Any remaining methanol will then have time to be excreted through the kidneys.[13][16][17]

Methanol itself, while poisonous (LD50 5628mg/kg, oral, rat[18]), has a much weaker sedative effect than ethanol.

Isopropyl alcohol is oxidized to form acetone by alcohol dehydrogenase in the liver but have occasionally been abused by alcoholics, leading to a range of adverse health effects.

Simple alcohols

The most commonly used alcohol is ethanol, C2H5OH, with the ethane backbone. Ethanol has been produced and consumed by humans for millennia, in the form of fermented and distilled alcoholic beverages. It is a clear, flammable liquid that boils at 78.4 °C, which is used as an industrial solvent, car fuel, and raw material in the chemical industry. In the US and some other countries, because of legal and tax restrictions on alcohol consumption, ethanol destined for other uses often contains additives that make it unpalatable (such as denatonium benzoate) or poisonous (such as methanol). Ethanol in this form is known generally as denatured alcohol; when methanol is used, it may be referred to as methylated spirits or "surgical spirits".The simplest alcohol is methanol, CH3OH, which was formerly obtained by the distillation of wood and, therefore, is called "wood alcohol". It is a clear liquid resembling ethanol in smell and properties, with a slightly lower boiling point (64.7 °C), and is used mainly as a solvent, fuel, and raw material. Unlike ethanol, methanol is extremely toxic: As little as 10 ml can cause permanent blindness by destruction of the optic nerve and 30 ml (one fluid ounce) is potentially fatal.[21]

Two other alcohols whose uses are relatively widespread (though not so much as those of methanol and ethanol) are propanol and butanol. Like ethanol, they can be produced by fermentation processes. (However, the fermenting agent is a bacterium, Clostridium acetobutylicum, that feeds on cellulose, not sugars like the Saccharomyces yeast that produces ethanol.) Saccharomyces yeast are known to produce these higher alcohols at temperatures above 75 °F (24 °C). These alcohols are called fusel alcohols or fusel oils in brewing and tend to have a spicy or peppery flavor. They are considered a fault in most styles of beer.[22]

Simple alcohols, in particular, ethanol and methanol, possess denaturing and inert rendering properties, leading to their use as anti-microbial agents in medicine, pharmacy, and industry.

Alcohols are classified into primary, secondary (sec), and tertiary (tert), based upon the number of carbon atoms connected to the carbon atom that bears the hydroxyl group. The primary alcohols have general formulas RCH2OH; secondary ones are RR'CHOH; and tertiary ones are RR'R"COH, where R, R', and R" stand for alkyl groups. Ethanol and n-propyl alcohol are primary alcohols; isopropyl alcohol is a secondary one. The prefixes sec- (or s-) and tert- (or t-), conventionally in italics, may be used before the alkyl group's name to distinguish secondary and tertiary alcohols, respectively, from the primary one. For example, isopropyl alcohol is occasionally called sec-propyl alcohol, and the tertiary alcohol (CH3)3COH, or 2-methylpropan-2-ol in IUPAC nomenclature is commonly known as tert-butyl alcohol or tert-butanol.

Alcohols have an odor that is often described as “biting” and as “hanging” in the nasal passages. Ethanol has a slightly sweeter (or more fruit-like) odor than the other alcohols.

In general, the hydroxyl group makes the alcohol molecule polar. Those groups can form hydrogen bonds to one another and to other compounds (except in certain large molecules where the hydroxyl is protected by steric hindrance of adjacent groups[28]). This hydrogen bonding means that alcohols can be used as protic solvents. Two opposing solubility trends in alcohols are: the tendency of the polar OH to promote solubility in water, and the tendency of the carbon chain to resist it. Thus, methanol, ethanol, and propanol are miscible in water because the hydroxyl group wins out over the short carbon chain. Butanol, with a four-carbon chain, is moderately soluble because of a balance between the two trends. Alcohols of five or more carbons (pentanol and higher) are effectively insoluble in water because of the hydrocarbon chain's dominance. All simple alcohols are miscible in organic solvents.

Because of hydrogen bonding, alcohols tend to have higher boiling points than comparable hydrocarbons and ethers. The boiling point of the alcohol ethanol is 78.29 °C, compared to 69 °C for the hydrocarbon hexane (a common constituent of gasoline), and 34.6 °C for diethyl ether.

Alcohols, like water, can show either acidic or basic properties at the -OH group. With a pKa of around 16-19, they are, in general, slightly weaker acids than water, but they are still able to react with strong bases such as sodium hydride or reactive metals such as sodium. The salts that result are called alkoxides, with the general formula RO- M+.

Meanwhile, the oxygen atom has lone pairs of nonbonded electrons that render it weakly basic in the presence of strong acids such as sulfuric acid. For example, with methanol:

Alcohols can also undergo oxidation to give aldehydes, ketones, or carboxylic acids, or they can be dehydrated to alkenes. They can react to form ester compounds, and they can (if activated first) undergo nucleophilic substitution reactions. The lone pairs of electrons on the oxygen of the hydroxyl group also makes alcohols nucleophiles. For more details, see the reactions of alcohols section below.

As one moves from primary to secondary to tertiary alcohols with the same backbone, the hydrogen bond strength, the boiling point, and the acidity typically decrease.

Alcohol has a long history of several uses worldwide. It is found in beverages for adults, as fuel, and also has many scientific, medical, and industrial uses. The term alcohol-free is often used to describe a product that does not contain alcohol. Some consumers of some commercially prepared products may view alcohol as an undesirable ingredient, particularly in products intended for children.

Alcoholic beverages

Alcoholic beverages, typically containing 5% to 40% ethanol by volume, have been produced and consumed by humans since pre-historic times.Antifreeze

A 50% v/v (by volume) solution of ethylene glycol in water is commonly used as an antifreeze.Antiseptics

Ethanol can be used as an antiseptic to disinfect the skin before injections are given, often along with iodine. Ethanol-based soaps are becoming common in restaurants and are convenient because they do not require drying due to the volatility of the compound. Alcohol based gels have become common as hand sanitizers.Fuels

Some alcohols, mainly ethanol and methanol, can be used as an alcohol fuel. Fuel performance can be increased in forced induction internal combustion engines by injecting alcohol into the air intake after the turbocharger or supercharger has pressurized the air. This cools the pressurized air, providing a denser air charge, which allows for more fuel, and therefore more power.Preservative

Alcohol is often used as a preservative for specimens in the fields of science and medicine.Solvents

Alcohols have applications in industry and science as reagents or solvents. Because of its relatively low toxicity compared with other alcohols and ability to dissolve non-polar substances, ethanol can be used as a solvent in medical drugs, perfumes, and vegetable essences such as vanilla. In organic synthesis, alcohols serve as versatile intermediates.Production

In industry, alcohols are produced in several ways:- By fermentation using glucose produced from sugar from the hydrolysis of starch, in the presence of yeast and temperature of less than 37 °C to produce ethanol. For instance, such a process might proceed by the conversion of sucrose by the enzyme invertase into glucose and fructose, then the conversion of glucose by the enzyme zymase into ethanol (and carbon dioxide).

- By direct hydration using ethylene (ethylene hydration)[30] or other alkenes from cracking of fractions of distilled crude oil.

Endogenous

Several of the benign bacteria[which?] in the intestine use fermentation as a form of anaerobic metabolism. This metabolic reaction produces ethanol as a waste product, just like aerobic respiration produces carbon dioxide and water. Thus, human bodies contain some quantity of alcohol endogenously produced by these bacteria.[citation needed]Laboratory synthesis

Several methods exist for the preparation of alcohols in the laboratory.Substitution

Primary alkyl halides react with aqueous NaOH or KOH mainly to primary alcohols in nucleophilic aliphatic substitution. (Secondary and especially tertiary alkyl halides will give the elimination (alkene) product instead). Grignard reagents react with carbonyl groups to secondary and tertiary alcohols. Related reactions are the Barbier reaction and the Nozaki-Hiyama reaction.Reduction

Aldehydes or ketones are reduced with sodium borohydride or lithium aluminium hydride (after an acidic workup). Another reduction by aluminiumisopropylates is the Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley reduction. Noyori asymmetric hydrogenation is the asymmetric reduction of β-keto-esters.Hydrolysis

Alkenes engage in an acid catalysed hydration reaction using concentrated sulfuric acid as a catalyst that gives usually secondary or tertiary alcohols. The hydroboration-oxidation and oxymercuration-reduction of alkenes are more reliable in organic synthesis. Alkenes react with NBS and water in halohydrin formation reaction. Amines can be converted to diazonium salts, which are then hydrolyzed.The formation of a secondary alcohol via reduction and hydration is shown:

Reactions

Deprotonation

Alcohols can behave as weak acids, undergoing deprotonation. The deprotonation reaction to produce an alkoxide salt is performed either with a strong base such as sodium hydride or n-butyllithium or with sodium or potassium metal.- 2 R-OH + 2 Na → 2 R-O−Na+ + H2

- 2 CH3CH2-OH + 2 Na → 2 CH3-CH2-O−+ + H2↑

- R-OH + NaOH ⇌ R-O-Na+ + H2O (equilibrium to the left)

The acidity of alcohols is also affected by the overall stability of the alkoxide ion. Electron-withdrawing groups attached to the carbon containing the hydroxyl group will serve to stabilize the alkoxide when formed, thus resulting in greater acidity. On the other hand, the presence of electron-donating group will result in a less stable alkoxide ion formed. This will result in a scenario whereby the unstable alkoxide ion formed will tend to accept a proton to reform the original alcohol.

With alkyl halides alkoxides give rise to ethers in the Williamson ether synthesis.

Nucleophilic substitution

The OH group is not a good leaving group in nucleophilic substitution reactions, so neutral alcohols do not react in such reactions. However, if the oxygen is first protonated to give R−OH2+, the leaving group (water) is much more stable, and the nucleophilic substitution can take place. For instance, tertiary alcohols react with hydrochloric acid to produce tertiary alkyl halides, where the hydroxyl group is replaced by a chlorine atom by unimolecular nucleophilic substitution. If primary or secondary alcohols are to be reacted with hydrochloric acid, an activator such as zinc chloride is needed. In alternative fashion, the conversion may be performed directly using thionyl chloride.[1]

Alcohols may, likewise, be converted to alkyl bromides using hydrobromic acid or phosphorus tribromide, for example:

- 3 R-OH + PBr3 → 3 RBr + H3PO3

Dehydration

Alcohols are themselves nucleophilic, so R−OH2+ can react with ROH to produce ethers and water in a dehydration reaction, although this reaction is rarely used except in the manufacture of diethyl ether.More useful is the E1 elimination reaction of alcohols to produce alkenes. The reaction, in general, obeys Zaitsev's Rule, which states that the most stable (usually the most substituted) alkene is formed. Tertiary alcohols eliminate easily at just above room temperature, but primary alcohols require a higher temperature.

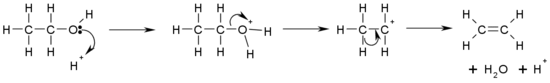

This is a diagram of acid catalysed dehydration of ethanol to produce ethene:

A more controlled elimination reaction is the Chugaev elimination with carbon disulfide and iodomethane.

Esterification

To form an ester from an alcohol and a carboxylic acid the reaction, known as Fischer esterification, is usually performed at reflux with a catalyst of concentrated sulfuric acid:- R-OH + R'-COOH → R'-COOR + H2O

Other types of ester are prepared in a similar manner — for example, tosyl (tosylate) esters are made by reaction of the alcohol with p-toluenesulfonyl chloride in pyridine.

Oxidation

Primary alcohols (R-CH2-OH) can be oxidized either to aldehydes (R-CHO) or to carboxylic acids (R-CO2H), while the oxidation of secondary alcohols (R1R2CH-OH) normally terminates at the ketone (R1R2C=O) stage. Tertiary alcohols (R1R2R3C-OH) are resistant to oxidation.

The direct oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids normally proceeds via the corresponding aldehyde, which is transformed via an aldehyde hydrate (R-CH(OH)2) by reaction with water before it can be further oxidized to the carboxylic acid.

Reagents useful for the transformation of primary alcohols to aldehydes are normally also suitable for the oxidation of secondary alcohols to ketones. These include Collins reagent and Dess-Martin periodinane. The direct oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids can be carried out using potassium permanganate or the Jones reagent.

The direct oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids normally proceeds via the corresponding aldehyde, which is transformed via an aldehyde hydrate (R-CH(OH)2) by reaction with water before it can be further oxidized to the carboxylic acid.

Reagents useful for the transformation of primary alcohols to aldehydes are normally also suitable for the oxidation of secondary alcohols to ketones. These include Collins reagent and Dess-Martin periodinane. The direct oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids can be carried out using potassium permanganate or the Jones reagent.

0 comments:

Post a Comment